Exploring the mixing-board aesthetic and new audiovisual relations.

According to Carol Vernallis in ‘The New Cut-up Cinema’(2013,p.35),

- “Music videos often showcase a mixing-board aesthetic, fluid, flexible forms in which individual parameters—a gesture, lyric, melodic hook, rhythm, edit, costuming touch, or prop—will come to the fore and fade away within a network of interlaced connections. It’s the way that musical materials are worked with on the mixing board.”

Through the attempts and experiments of music video directors and editors in resetting images and sounds, the unique audiovisual relationship is developed. (Vernallis, 2013) In classical cinema, sound is subordinated to the image. In modernist cinema, sound becomes a new kind of image. The post-cinematic media has brought changes to the familiar audiovisual contract. In television and video, visual images tend to approach the condition of sounds more closely. (Shaviro, 2016)

Steven Shaviro also states in ‘Splitting the Atom: Post-Cinematic Articulations of Sound and Vision’ that although sound could come from a certain place, it has no location. When a sound is heard, it instantly fills the entire space to which it can travel. The filling of space allows the sound to reverse the sequential order of the visual narrative, “lends itself to the multiplicity of the spatialized database aesthetic”. (Shaviro, 2016, p.19)

In cinema, sound temporalizes the image. But in post-cinematic and digitized music videos, the function of sound is to release the image from the continuity of temporality and to establish a non-linearity and non-narrative.

The diverse music video techniques not only demonstrate a mixing-board aesthetic, but also produce and explore new audiovisual relations. Rihanna’s music video ‘Rude Boy‘(2010), for example, features a large number of composite images that stimulate the viewer’s sensibilities. Rude Boy uses a lot of brightly coloured shots and cuts them quickly to create a strong visual clash. Notably, Rude Boy uses very two-dimensional visual effects, using image matting to overlay the dynamic figures (such as Rihanna playing drums or dancing) (see Figure 1 & 2) or other elements (moving lips) (see Figure 3) together with abstract graphic background. This visually abandons three-dimensional space.

And the sounds, that is, the repetitive rhythms, lyrics and melodies of the songs, create a circulation along with the ever-changing, generative images, which “creates a sense of visual polyphony and even of simultaneity”. (Shaviro, 2016, p.40) At this point the image no longer serves a linear narrative structure, but creates a discontinuous digital resonance.

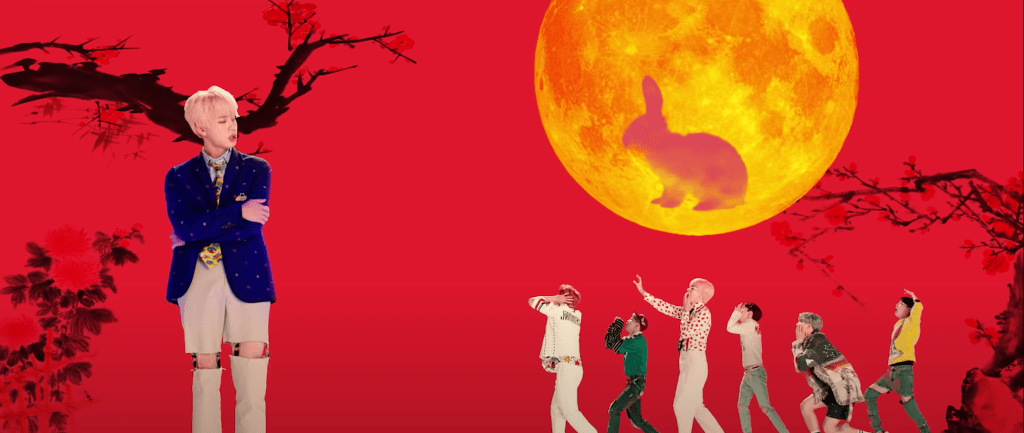

Inspired by Rude Boy, I was personally interested in the visual style of two-dimensionality in music videos and found a few other examples of employing such a technique. I will show some shots below.

The music video ‘Dumb Dumb‘ (2015) by the Korean girl group Red Velvet also features a number of creative, two-dimensional scenes. See Figure 8 for example, where the keyed images of people are overlaid one after the other on a two-dimensional background in time with the repetition of the word “dumb” in lyrics.

As well as Figures 9 and 10 also present a very interesting visual effect, with the individual portraits of the girls stacked on top of each other, still using a single-coloured, two-dimensional background. The portraits, however, are rotating 360 degrees, which gives the viewer a visual experience that is both two-dimensional and three-dimensional.

Combined with the repetitive, brainwashing lyrics and simple melodies of the chorus, the music video ‘Dumb Dumb‘ creates a bewildering but fascinating world. Both the images and the music of the video take the viewer out of the continuity of the traditional narrative, where temporality and spatiality are blurred. Viewers are rewarded with many immediate, audiovisual sensory experiences.

Overall, with new technologies and new media, music videos now have the capacity to create more innovative visual effects through digital techniques. Post-cinematic music videos have more ways to explore new audiovisual relations and expand aesthetic diversity.

References:

- Shaviro,S. (2016) ‘Splitting the Atom: Post-Cinematic Articulations of Sound and Vision,’ in Denson and Leyda (eds), Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st-Century Film (Falmer: REFRAME Books, 2016). ISBN 978-0-9931996-2-2 (online). pp.19. pp.40 Available at: https://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/post-cinema/3-4-shaviro/?pdf=145 (Accessed on: 24 November 2022)

- Vernallis, C. (2013) ‘The New Cut-up Cinema’, Unruly Media: YouTube, Music Video, and the New Digital Cinema, in The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics. Oxford University Press. pp.35.

By YiXi Zhao (33659283)

First written on 24/11/2022

Re-edited on 28/11/2022

Leave a comment