“Don’t you address me unless it’s with four letters.”

Revolutionary in every sense of the word, Kendrick Lamar is inarguably one of the greatest ever to grace hip-hop. Honestly, there is every reason for him to call himself the G.O.A.T., The King, and much more.

However, after his incredible 2017 release of DAMN., Kendrick took a much-deserved four-year hiatus from the art. Eventually, he featured on his cousin Baby Keem’s third studio album, ‘The Melodic Blue’ in 2021. Seven months after this, he cryptically announced his own upcoming studio record – ‘Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers’ – in typical K.Dot fashion, while throwing shade at a fan who made fun of him for not releasing music in a while.

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.jshttps://t.co/YVE5bZOBL2 https://t.co/UywGGKExb1

— Kendrick Lamar (@kendricklamar) April 18, 2022

The album opens with ‘United in Grief’, with a female melodic VoiceOver telling addressing Kendrick. “Tell them the truth,” she says. Presumably, ‘them’ is in reference to the audience, and the truth will eventually be relayed over the one-hour eighteen-minute album. The main theme of the record is a changed Kendrick – one that has held the ‘crown’ for far too long, and cannot wait to get rid of it. He symbolises that through the album art by using a crown of thorns, one that will pain, bleed, and pierce his skin, much like the metaphorical one he has on.

Arguably the headlining song on this album comes immediately after United in Grief, though, called, N95. It accompanies a sensational, emotional music video, as is tradition for Kendrick. Directed by Dave Free and Kendrick himself, it is, in my opinion, the most gripping piece of visual art the American rapper has produced, topping his own chart-breaking, tears-inducing works like HUMBLE. and King Kunta. It is a masterclass in post-cinematic effect – subtle as it may be -, while also maintaining a retro look Kendrick has adopted in recent times.

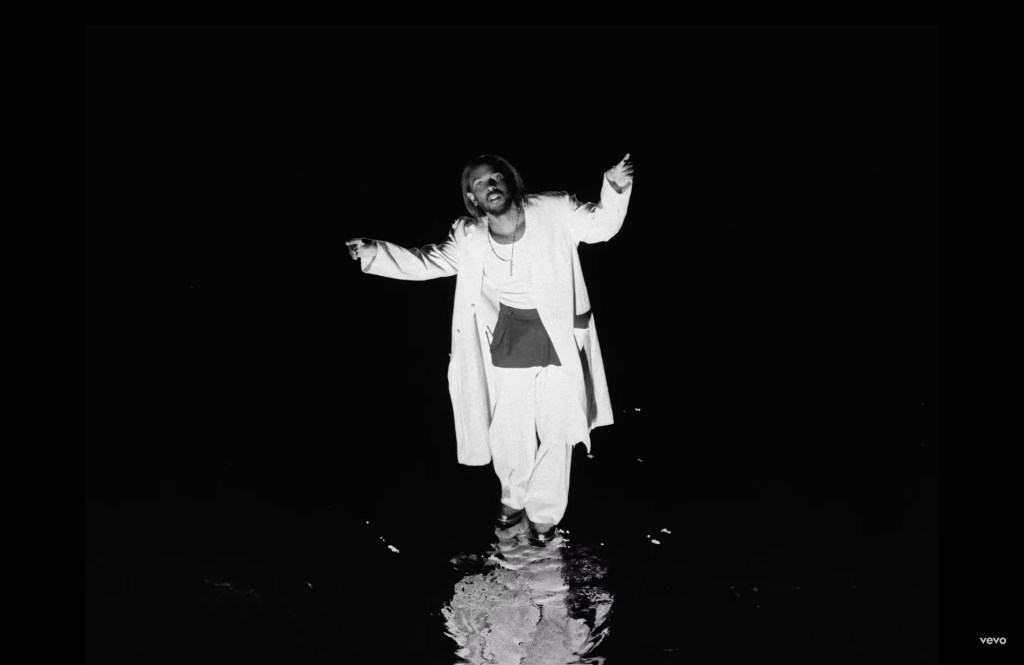

The video opens in a 3:2 aspect ratio, with a black kid overlooking an ocean, which eventually reveals the first taste of post-cinematic/VFX. Kendrick is floating above the water, posed like Jesus Christ’s crucifixion, reciting some “true stories”. It is not beyond Kendrick to refer to himself as a god – or the son of, in this case -, and he uses post-cinema to achieve that look, talking presumably to the boy – Kendrick’s past – sitting on the shore. The end result of his floating body looks very unnatural, rather cardboard-like, but Kendrick uses the post-cinema here as an exaggeration, to send a message across; not to elevate the visual cues of his video.

It also serves as a contrast to the main theme of the album, where he wants his listeners to know that he is ‘human’, after all, and not the god fans often acclaim him to be.

His floating like Jesus also, in a way goes in tandem with the ‘new world’ he seeks to address, which can be interpreted in two ways — a post-COVID Earth or his audience following his hiatus. The former is evidently the more plausible theory, especially in reference to the song title itself – N95 -, which was a type of mask people wore during COVID to protect themselves from contagious air.

That said, N95 does not lack ‘special effects’ used to grasp the attention of the audience in any way, shape or form. In fact, immediately after this opening shot, Kendrick uses an old-but-reliable method of grounding the viewer, through quick flickering lights. The visual is that of a very conventional rap video — black and white, with a woman, subtly dancing to the lyrics. That scene then quickly bursts into a black flash that serves as a transitional sequence to both the video and music. A clapperboard comes in to reveal that Kendrick is not, in fact, there, and only edited in later on – symbolising the ‘fakeness’ of the music industry. It is also a hit out at the overdone post-production ‘tricks’ themselves, and the deep fakes he has used in a previous music video.

Barely 30 seconds in, we get another taste of creative post-production in the video as Kendrick, talking to himself, asks his past self to ’take off the fake and unimportant stuff’ like designer bags, fabricated streams, the clout, because “there is a real world outside”. Immediately afterwards, a hammer comes in to break the screen over the lyrics “take off your idols”. Glass shatters and falls on the floor, revealing that Kendrick – one of the biggest ‘idols’ in the world of hip-hop and music, in general – has been taken off. Or rather, he wants to step off the pedestal himself. He is too scared to do that, though, which is represented by his flinch just before the hammer hits glass.

“Take off the cop with the eye patch” falls with the visual of Kendrick with his eyes censored while he’s holding a pigeon. Presumably, the ‘cop’ here is Derek Chauvin – the man responsible for the death of George Floyd. The censor is, in my opinion, a reference to the lyric about the cop being half-blind (with an eyepatch), and only seeing crimes committed by black people.

We are treated to more post-cinematic effects later on in the video, through quick flashes and light grading, but another shot that stands out is across the lyrics, “The world in a panic, the women is stranded, the men on the run. The prophets abandoned, the lord take advantage…”. Kendrick is shown running from a group of men, with blur uses to show his high speed. Further, as soon as the song says, “prophets abandoned”, the words, “THIS SHIT HARD” pop on the screen (not for the first time), which is also a double entendre. It obviously tries to say that the song goes hard – meaning it is good -, but also that being the artist he is, and a saviour/cultural icon is difficult.

In terms of colour and lighting, it is right up to the standards of any typical Kendrick video. The visuals are constantly pleasing, so viewers get a deeper sense of art even if each frame does not have a specific meaning. He uses black and white shades to create contrast, helping each frame pop out visually. It also plays well with the themes of race and colour he often discusses in his art.

Within four months, Kendrick went from asking people to only address him as the ‘GOAT’ to begging the same fanbase to stop. He uses post-cinematic affect to send his point across in what is one of the best visuals that will ever accompany the music. An art form meeting another to create a holistic experience, and so much more.

REFERENCES:

- genius.com/Kendrick-lamar-n95-lyrics (2022)

- Diane Railton and Paul Watson (2011), ‘Music Video in Black and White: Race and Femininity’, Music Video and the Politics of Representation

Written by Udhav Arora (33766290)

Leave a comment