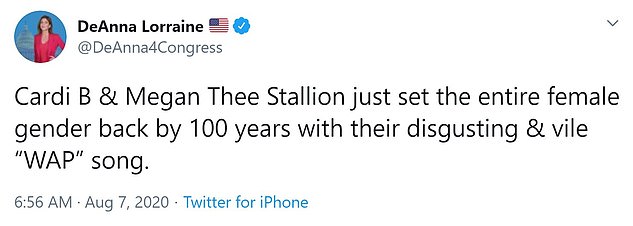

In August 2020, Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion released the music video for their song W.A.P. The song was a smash hit but sparked controversy for its sexually explicit visuals and lyrics. This controversy caused discussions on whether the song’s portrayal of women is a regressive representation or feminist empowerment.

Arnold et al. explains regressive representations as music videos which “promote overtly sexualised images of women in particular.” (Arnold et al. 2017, p9). Critics argued that having Cardi B and Megan wearing very little clothing, using phallic imagery of snakes and calling themselves ‘whores’ were examples of degradation and sexualisation. By using Colin Tilley, a male director, perpetuates the male gaze on these female bodies. “One-way women and girls are taught about femininity in music videos is through the ways characters are filmed (Jhally, 2007, p6).” For example, the camera in W.A.P. can often pan up and down the artist’s bodies, zooming in and lingering on their cleavage or bottom. They are encouraging the viewers to leer at them. This leering of men at women’s bodies epitomises Mulvey’s (1975) idea of the male gaze.

The opposing side argues that W.A.P. is an expression of women’s autonomy similar to the work of Madonna in the 1990s, “who openly challenged the music industry and its tendency to present women as objects of sexual desire” (Arnold et al. 2017, p12). Needleman from Boston University argues, “W.A.P has become an anthem for Black women empowerment, autonomy, and independence. Despite the pushback, women throughout the country have been motivated to take ownership over their sexuality.” An example of this ownership is seen through the hashtag W.A.P TikTok challenge, which has over 20 million uses. The music video has a male director, Cardi B and Patientce Foster, and the creative directors. The three worked as a unit to create this project.

Speaking on the male and female gaze, Brown says, “But what is the female gaze? There is no one accepted definition. It often used to mean simply “art by women”, but I think a more accurate definition would be art with a feminist sensibility.” Considering W.A.P’s feminist messaging of autonomy and reclamation, it is arguable that it is a music video from the female gaze.

Sarah Angel Majeed

33729881

Bibliography

Arnold, Gina, et al. Music/Video Histories, Aesthetics, Media. London Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

Aubrey, Jennifer Stevens, and Cynthia M. Frisby. “Sexual Objectification in Music Videos: A Content Analysis Comparing Gender and Genre.” Mass Communication and Society, vol. 14, no. 4, July 2011, pp. 475–501, https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2010.513468.

B, Cardi. “Cardi B – WAP Feat. Megan Thee Stallion [Official Music Video].” Www.youtube.com, Aug. 2020, youtu.be/hsm4poTWjMs?si=mAiySaVKuqKZPr74. Accessed 27 Nov. 2023.

Bragg, Ko. ““WAP” and the Politics of Black Women’s Bodies.” The 19th, 21 Mar. 2021, 19thnews.org/2021/03/wap-and-the-politics-of-black-womens-bodies/.

Brown, Grisela Murray. “Can a Man Ever Truly Adopt the Female Gaze?” Www.ft.com, 4 Jan. 2019, http://www.ft.com/content/4e29215a-0f40-11e9-a3aa-118c761d2745.

Mahdawi, Arwa. “The WAP Uproar Shows Conservatives Are Fine with Female Sexuality – as Long as Men Control It | Arwa Mahdawi.” The Guardian, 15 Aug. 2020, http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/aug/15/cardi-b-megan-thee-stalion-wap-conservatives-female-sexuality.

Needleman, Taylor. “Misogynoir in Media: How the Public’s Reaction to “WAP” Impacts Black Women | Deerfield: Journal of the CAS Writing Program.” Www.bu.edu, http://www.bu.edu/deerfield/2023/04/26/needleman1/.

Ross ’21, Julia. “WAP – Women Empowerment or Objectification?” The Advocate, 11 Nov. 2020, theacademyadvocate.com/5528/opinion/wap-women-empowerment-or-objectification/.

VanDyke, Erika. “Race, Body, and Sexuality in Music Videos.” Honors Projects, 1 Jan. 2011, scholarworks.gvsu.edu/honorsprojects/69/.

Leave a comment