– Red Burgess –

The relocation of the televisual experience into more personal spheres of social operation, such as phones, laptops, and other personal devices, reflects that the contemporary era of television is controlled more by the individual than ever. As Guy Rustad highlights,

““In similar ways to how daytime programming adapted to the flow of the daily life of the housewife, understanding how television producers adapt to the rhythms and flows of the audience’s daily digital networked lives, in order to create new aesthetic and cultural forms,” illustrates the evolving and transformative nature of contemporary ‘television’.

(Rustad 2018:71)

Where media consumption was once mediated solely by the interests of televisual networks and media producers, post-modern consumer culture now, more than ever, acts as a highly individualised experience (Lotz 2014). Capitalist realism situates individualism as a core principle of the free-market’s development (Fisher 2022: 24), thus culture has shifted in most recent decades toward personalised technologies, of which internet distributed media now circulates more freely than the now seemingly archaic commercial television. As Amanda Lotz describes,

“The increased control over how, where, and when to view, provided by digital video recorders (DVRs), DVDs, electronic programming guides (EPGs), digital cable boxes, laptops, smartphones, and tablets, expanded the convenient use of television.”

(Lotz 2014:54)

This technological transition marks therefore, a trend in the relocation of cultural consumption to the confines of individualised devices that allow the user to the “tools to both time-shift and place-shift,” (Lotz 2014:54) something that Lotz describes as having “far greater a desirability than the ability to view live television outside the home.” (Lotz 2014:54)

One counter argument to this however, directs attention toward the implementation of new algorithms across digital platforms which, while designed to cater to the preferences of the individual, are still largely impacted by the economic interests of the platform and it’s content creators.

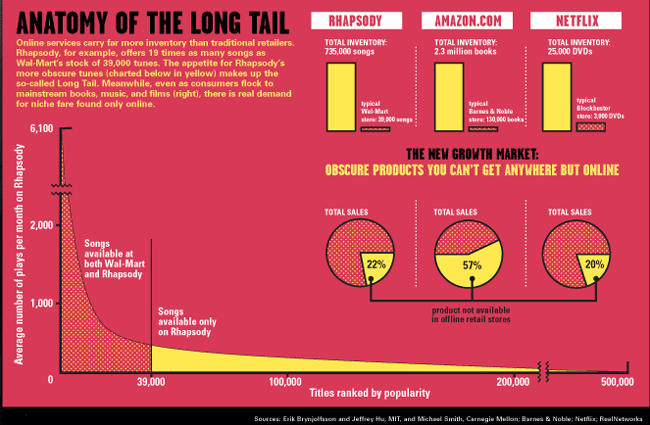

For Kevin McDonald, Netflix embodies the post-modern era of television as it facilitates “the long tail [of which signifies] the growing importance of niche markets and the subsequent shift from exclusively relying on massive successful commodities to more modestly successful commodities that generate value over longer periods of time,” (McDonald, 2016, 205). This economic framework directly impacts the consumption of digital culture, as with the example of Netflix, both the platforms programming and user interface “encourage longer periods of viewer engagement,” (McDonald 2016).

As facilitated by the capitalist free-market, lower production and distribution costs have enabled investment in seemingly unprofitable commodities that with time, generate profit (Anderson 2006). This format is reflected across both emerging and established brands such as Amazon and Temu, the former exemplifying the exploitation of low-cost employment and the latter exemplifying the exploitation of low-quality production (Gentzkow 2018: 10).

While it is true that “the contemporary experience of television reception is becoming more personal, ephemeral, mobile and instant than ever before,” (Rustad 2018:72) wider technological and cultural practices, with specific reference to the emergence of “AI informed algorithms” (Gentzkow 2018: 4) still remain dominantly mediated by what Mareike Jenner identifies as “matrix media […] where viewing patterns, branding strategies, industrial structures” (Jenner 2016: 260) cumulatively influence the way society and the individual interact with each other and subsequently, how wider culture transforms as a result.

———————————————————————–

References

Rustad, G. (2018)

Lotz, A. (2014) Theorising the Nonlinear Distinction of Internet-Distributed Television, in Portals: a treatise on internet-distributed television. Maize Books.

Fisher, M. (2009) Capitalist realism: Is there no alternative?. Zero Books: United Kingdom.

McDonald, K. (2016) The Netflix effect: technology and entertainment in the 21st century. Bloomsbury Academic: New York.

Anderson, C. (2006) The Long Tail. Hyperion Books: United States.

Jenner, M. (2016) Netflix and the re-invention of television. Palgrave Macmillan: Switzerland.

Gentzkow, M. (2018). Media and artificial intelligence. Working Paper.

Leave a comment