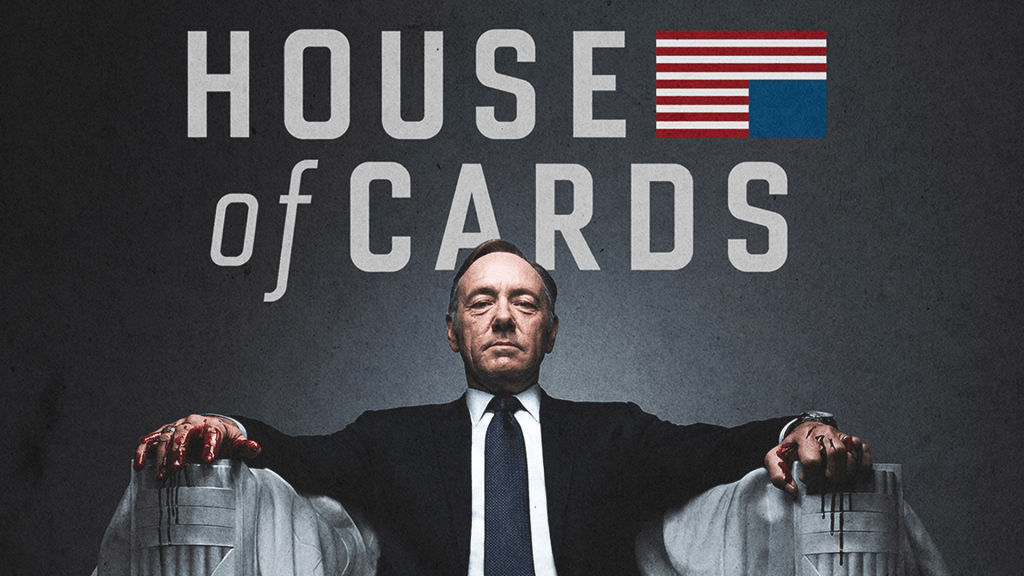

For many decades, it has been clear that a plethora of films and television shows have interacted with modified so-called spectator experiences. One may claim that the proportion of moviegoers has reduced considerably as a result of Netflix. Kevin Spacey, the show’s lead, praised Netflix however as a source of highly valued and inventive entertainment during a speech at the 2013 Guardian Edinburgh Television Festival promoting the first original series created by a studio for Netflix, House of Cards (2013 – 2018). With that in mind, Spacey went on to equate political plays to movie theatres, asking rhetorically, “Is thirteen hours watched as one cinematic whole really any different from a film?”. Indeed, as John Ellis points out, “many TV scholars seem to be obsessed with Netflix and binge-watching, but the lockdown experience dramatically demonstrated the continuing importance of broadcast TV”.

Since its inception in 1997 as a mail-based rental service, Netflix has paved the way for the global implementation of a commercial television service and has begun producing some of its pristine, authentic content with the goal of reaching people of all ages and backgrounds around the world. Given its online viewer subscriptions continuously increasing, particularly during the 2010s, which is often referred to in this case as the “Golden Age of Television,” Netflix has also earned a philosophical reputation for the evolution of its initial content to cater to all audiences. As a result, we may be able to agree that, as Chuck Tryon remarked, “Netflix has [perhaps] situated itself as the future of television.” (Tryon, 2015).

In conclusion, while the democratisation of Netflix has given users more choice and authority over their viewing preferences, new challenges have surfaced. Netflix’s massive popularity and cultural clout effectively make it a gatekeeper in its own right; the streaming juggernaut holds significant bargaining power over content creators and distributors, including the ability to restrict specific titles or sign exclusive partnerships. However, while the experience may be more personalised to specific users, it may also discourage people from participating in common events, an influence that is already enhanced by social alienation norms.

By George Lambert

Bibliography:

Ellis, J. (2020) “Provocations, I: What do we need in a crisis? broadcast TV!,” Critical Studies in Television: The International Journal of Television Studies, 15(4), pp. 393–398. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1749602020959863.

Tryon, C. (2015) “TV got better: Netflix’s original programming strategies and Binge Viewing,” Media Industries Journal, 2(2). Available at: https://doi.org/10.3998/mij.15031809.0002.206.

Leave a comment