Cunningham and Craig (2019, p. 65) argue that content creator labour on platforms like YouTube is both empowered and precarious. “One distinguishing feature of creator labor that requires attention is that it, by necessity, works within an algorithmic culture” (Cunningham & Craig, 2019, p. 65).

Every creator must operate within the algorithmic constraints of platforms and constantly changing guidelines regarding content categories, intellectual property, and content standards. Monetisation on YouTube means creators can make money from their videos if they meet the guidelines.

YouTube has different categories. Gaming creators play video games through gameplay and walkthroughs. Many of these YouTubers work on multiple platforms to generate income and reach. For example, FIFA YouTuber Danny Aarons streams on Twitch during the week, does TikTok shorts, and uploads to YouTube.

Film clips are shown on YouTube, and channels like Movieclips have 60 million subscribers. There are film/TV review channels and reaction videos. TV series like The Office use YouTube to upload clips from their show, which generates views and revenue.

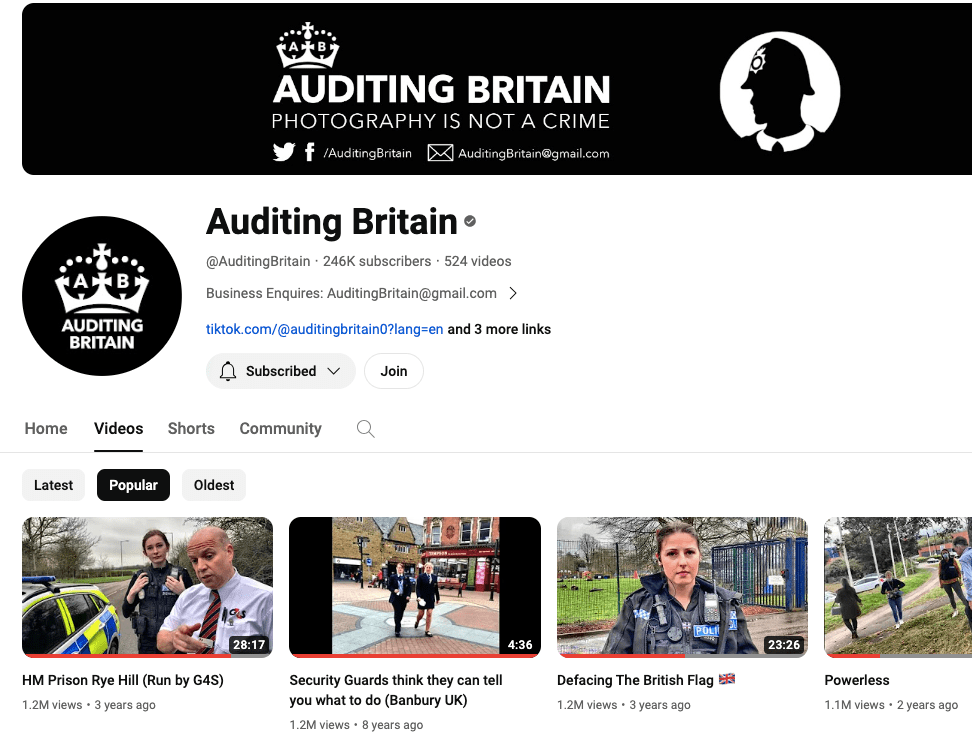

“Burgess […] identified the distinctiveness of ‘entrepreneurial vloggers’ on YouTube, which operates as a ‘key site’ where the discourses of participatory culture and the emergence of the creative empowered consumer have been played out’” (Cunningham & Craig, 2019, p. 77). Auditors are a key example; they have a big following, they visit workplaces and industrial estates around the country, and they visit companies off guard by their daily vlogs, which sometimes create aggressive responses; an example is Auditing Britain.

DIY creators show how to make things yourself, from toys to cooking. There are educational and beauty channels that promote product reviews and makeup tutorials. There are wellbeing channels that deal with physical and mental health. Music channels are a huge part of YouTube. Channels such as Vevo and artists upload their music videos; for example, Ariana Grande has a huge following. Some YouTubers have experience, like KSI. Others with no experience, like Auzio, became big in YouTube gaming.

Social media platforms are frequently seen as exploiting creators’ expressive practices, reducing their creativity. A lot of content is either country-blocked or demonetised. The term ‘creators’ is neutral and preferred by content creators; it is professionalizing and commercialising native social media users who produce and share original content to develop, market, and make money from their media brand both offline and on social media.

Cunningham & Craig (2019, pp. 70, 79) suggest most content creators are in-between amateurs and professionals. They create their content and market it through social media and YouTube. They’re doing both online and offline editing, live-streaming and pre-recorded content. They consider them to be both precarious and aspirational. There are billions of users on YouTube, millions of subscribers, and billions of views. The growth of YouTube has been huge; examples are Sidemen charity football matches, Logan Paul and KSI, and the YouTube boxing era.

By James Farrell

References

Cunningham, S., and Craig, D. (2019) Social Media Entertainment: The New Intersection of Hollywood and Silicon Valley. New York: New York University Press.

Leave a comment