“Spirited Away” (:千と千寻の神隠し) is a classic animated film directed by the famous Japanese director Hayao Miyazaki and produced by Studio Ghibli. It was released on July 20, 2001. The film tells the story of a 10-year-old girl Chihiro Ogino who strayed into a mysterious ghost world with her parents while moving. In this world, her parents were turned into pigs because of their greed. In order to save her parents, Chihiro must find a job in the rest house “Yuya” run by Grandma Yuri, and grow up in this fantasy and challenging environment. She met many strange characters, including the white dragon, the faceless man, and the river god, and went through a series of adventures. In the end, she found her name, saved her parents, and returned to the real world.

Chaos Cinema is a film style that aims to induce a strong sensory response from the audience through visual and auditory shocks. This style is usually extremely obvious in action movies and science fiction movies. However, how does an animated film embody the Chaos Cinema theory?

1) Non-linear narrative

Animation works often use an indirect narrative structure, telling stories through different timelines and perspectives. “Spirited Away” shows the complex relationship between multiple characters and events through Chihiro’s experience in the spirit world, showing Chihiro’s growth and exploration in the spirit world, and enhancing the depth and layering of the narrative. This narrative method requires the audience to actively participate in the story and interpret the connection between different plots. It is a manifestation of the challenge to the traditional narrative relationship in Chaos Cinema theory.

2) Fast editing and fragmented vision

In the interactive scene between Chihiro and the faceless man, the camera switches at intervals, creating a tense and chaotic rhythm. This fast editing makes the audience feel a sense of urgency when watching, and also reflects the anxiety and uneasiness of the characters.

3) Sound design

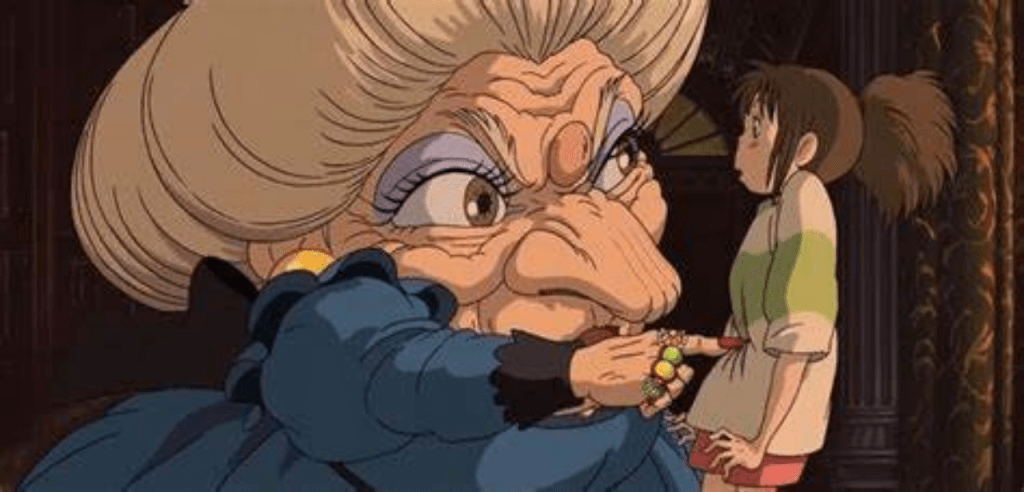

The sound design in the film plays an important role in balancing the visual chaos. When Chihiro enters the oil house, the background sound effects and character dialogues help the audience understand the plot, even if the picture itself is blurry. This inconsistency between sound and vision is a major feature of the Chaos Cinema, which keeps the audience tense in their senses.

4) Symbolic metaphors

The film is full of symbolic images, such as the bridge leading to the oil house symbolizing the boundary between human society and the world of gods. Haku reminds Chihiro to “hold her breath” when crossing the bridge, which reflects her state that she has not yet been accepted by the world of gods. In addition, the balls given to Chihiro by the river god symbolize “returning to the origin”, emphasizing the importance of purification and self-cognition. These symbolic metaphors enrich the connotation of the film and make it go beyond a simple fairy tale.

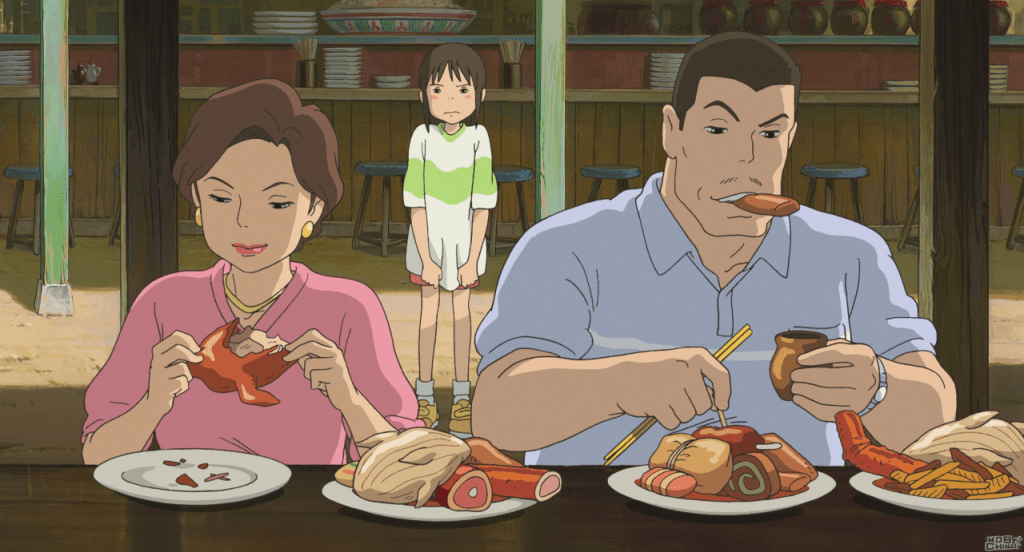

5) Exploration of desire

The film deeply explores the theme of desire and greed, and the character of the faceless man embodies the terrible consequences of the expansion of desire. He was originally an invisible existence, but with the thirst for gold, he became huge and eventually devoured others. Through the contrast between Chihiro and the faceless man, the film shows the struggle between keeping the original intention and losing oneself, reflecting people’s pursuit of material desires in modern society and the negative effects it brings, and it is also a manifestation of the exploration of the complexity of human nature in chaotic films (Stucki, T. 2014).

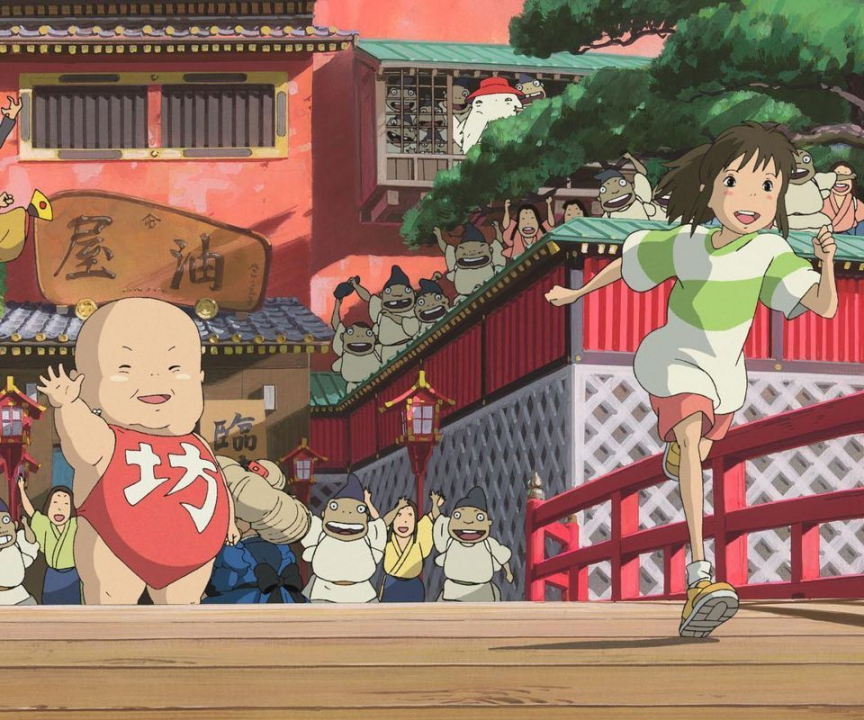

6) Binary opposition

There are multiple binary opposition structures in the film, such as the opposition between “self” and “id” (UTAKER, A. 1974). Chihiro undergoes an identity transformation in the world of spirits. She changes from “Chihiro” to “Chihiro”, a process that symbolizes her inner struggle under the pressure of the external environment. In the end, she finds herself through hard work and keeping her original intention. This growth process reflects the inner conflicts and changes of characters commonly seen in chaotic movies.

7) Social criticism

“Spirited Away” also reflects the criticism of modern social and economic phenomena. At the beginning of the film, Chihiro’s family breaks into the world of gods regardless of the environment, symbolizing the modern people’s disrespect for nature and traditional culture. This conflict is not only the background of personal growth, but also a reflection on the values of contemporary society (Stucki, T. 2014).

Through these elements, we can find that whether from the technical level or the content conception level, “Spirited Away” is a “chaotic movie” with profound philosophical and social criticism. It tries to challenge the audience’s cognition of reality, desire and self.

By: Jingwen Lei

References:

·Stucki, T. (2014). Animation as a medium of socio-cultural critique: thematic development in Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away (2001) (Doctoral dissertation).

·UTAKER, A. (1974) ON THE BINARY OPPOSITION. Linguistics, Vol. 12 (Issue 134), pp. 73-93. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.1974.12.134.73

Leave a comment