The most prominent trait in contemporary films is their ‘post-cinematic affect’. As Shaviro (2010) explained the ‘post-cinema affect’, is a ‘structure of feeling’, and all showed in those films mentioned in the article linked to their expression. Turning to the discussion of Aftersun, the part that got the highest appearance is this film involves huge energy of emotional affecting. Even though this film may not be a typical post-cinema, both the fragmental images, multiple narratives, and other traits can make this film exemplify the ‘post-cinematic affect’ or it can be explained by ‘post-cinema’. There is a specific sequence shows the methods that the director used to create the affective in film and this explores how post-cinema can generate affect and emotion.

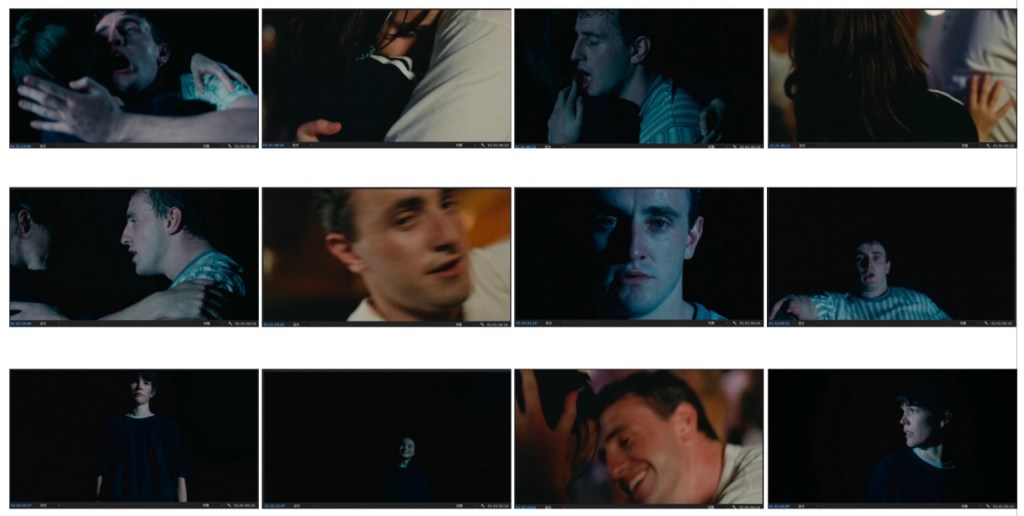

In this sequence, one scene of featuring the female teenage protagonist and her young father dancing joyfully amidst a lively, well-lit crowd on the final night of their holiday, and the other showcasing the adult protagonist as she encounters her father, now alone, dancing in a dimly lit dance club set within an imaginary field. This film skillfully uses a simple yet effective flash-black transition. The audience is guided by the flickering lights as they witness the father’s transition from a state of happiness in the holiday memories to a state of pain in the dimly lit dance club within the realm of imagination. In doing so, the director employs a unique and creative presentation style that enables the audience to readily accept and differentiate between the varying depictions of the protagonist ‘s father in her teenage and adult years. What further enhances this storytelling technique is the continuous appearance of the young father in both the real memories and the imaginary field. This continuity ensures a seamless narrative transition between these two distinct time periods. It allows for the establishment of an inter-temporal conversation between the father and daughter within the imaginative setting.

Additionally, this scene points the last time the adult protagonist enters the imaginary world. Even though the teenage protagonist’s image directly confronts her father’s growing sadness, neither the grown-up nor the teenage protagonist can rescue the young father trapped in his painful darkness. This scene centers on the director’s exploration of the father-daughter relationship, showing happy moments shared every day, but also the father’s struggle to hide his troubles from his daughter and bear them alone. It depicts a father-daughter bond that is both close and somewhat distant, as the father tries to protect his daughter from negativity while dealing with it alone.

Aftersun 1:29:37-1:32:30

The film establishes this special space for breaking the time-space and combining the present and past memory which seems chaotic, but according to Yavuz (2024), the director uses this kind of method to spread the uncertainty and vagueness without a stable position for the audience to stand which also can evoke audience’s feelings in their blurry memory. In this explanation, it made Deleuze and Guattari, ‘blocs of affect’ could be realized because the emotion shown in the film continuously stimulates affective through the common space setting, and this provides a visible method to show the complicated of affecting as Shaviro (2010)claimed the emotion of affecting cannot be represent by any kind of representations. This post-cinematic film articulates in a suitable way to make the affecting in a visible and specific space with emotion.

References:

Shaviro, S. (2010). ‘Post-Cinematic Affect: On Grace Jones, Boarding Gate and Southland Tales’, Film-Philosophy, 14(1), pp. 1–102. doi: 10.3366/film.2010.0001

Yavuz, D. (2024). ‘The Use of Memory in Aftersun as a Breakthrough in Telling Coming-of-Age Stories in Cinema’, Cinematic codes review. Hephzibah: Anaphora Literary Press, 9 (2), p.56-69

Wenyu Li 33831990

Leave a comment