When Bridgerton was released on Netflix, I remember a lot of people loving it for its period-drama aesthetics and creating an imagined world with a diverse cast. Twitter went on a frenzy with the scandalous plot twists along with people swooning over the lead actors. However, underneath all the fanfare for this beloved series by Shondaland, Bridgerton raises some important questions on inclusivity and our viewing experience.

In Theorizing the Nonlinear Distinction of Internet-Distributed Television, Amanda Lotz (2017) argues that Netflix has showcased a fundamental shift in how television is viewed and consumed. Its transnational, non-linear infrastructure enables the content to transcend borders, creating a wide range of viewers with varied tastes. Bridgerton is almost like a manifestation of this strategy, blending the familiarity of period dramas with diversity and spectacle in order to create mass appeal. With the whole season dropping at once, it also encourages binge-watching which as Mareike Jenner mentions, creates a more intense but ephemeral relationship with content (Jenner, 2018). This can play out in a way in which the viewers focus primarily on specific plot lines in the series and overlook the subtler themes. While Netflix’s data-informed creative decisions do identify untapped markets and cater to diverse audiences, one could argue that it could lead to “content by design” which caters primarily to a show’s marketability. Bridgerton falls in-between this tension.

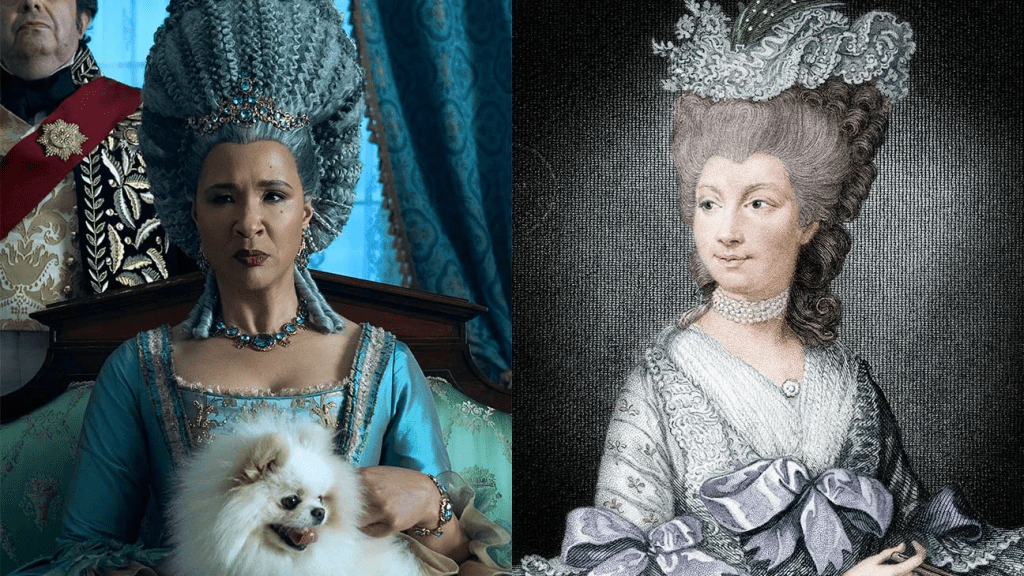

The show gives a nod to the presence of otherwise erased demographics from popular narrative, like the existence of black people in Georgian England. These choices do bring some form of authenticity to the period piece but the show’s broader portrayal of race tends to gloss over the complexities of such identities in a society that had been entangled with colonialism and slavery. It can be argued that, at the end of the day, it is historical fiction and that with characters like Queen Charlotte and Simon Basset, there is a welcome change in terms of inclusivity. However, the utopian ideal in the show does coexist with hints of (not so explicit) racial struggle with characters like Will Mondrich and Mary Sharma. Even the character of Queen Charlotte is shown as a historical anomaly, hinting that there was a systemic change in the fictional society but does not dive deeper into its implications.These moments, in some way, do suggest that race matters in Bridgerton but it moves on to its utopian fantasy by avoiding addressing these issues.

Ultimately, the Netflix model thrives on global appeal, and Bridgerton does epitomise this strategy. As Jenner(2016) had mentioned, there are latent market-driven algorithms in place which leads to the question of genuine cultural engagement for such shows. While there are debates about representation in this new age of streaming being marketable or meaningful, I do think that Bridgerton is unique in its refreshing take of period dramas. The show does have its own set of limitations in terms of nuances to representation in fiction, but it still is a fictional series about finding love. As we move further into the era of streaming, the show’s success and its drawbacks could offer significant insights into the intricacies of inclusivity, storytelling and internet-distributed television.

Reference List:

Jenner, M. (2018).Introduction: Binge Watching Netflix. Netflix and the Reinvention of Television. 109-118.

Jenner, M. (2018).Introduction: Netflix and the Re-invention of Television. Netflix and the Reinvention of Television. 1-31.

Lotz, A. D. (2017). Theorizing the Nonlinear Distinction of Internet-Distributed Television. Portals: A Treatise on Internet Distributed Television. Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9699689

Paarth Pande, 33811391

Leave a comment