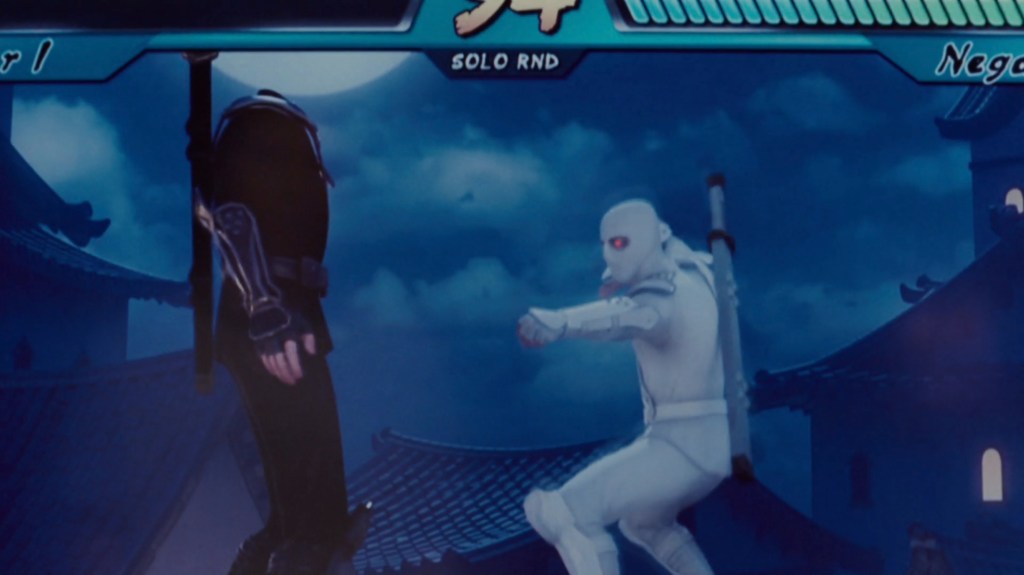

Scott Pilgrim vs. the world (2011) is full of conventions from games and manga, etc. For example, there are graphics such as ‘Ding, Ding’ and ‘SMASH?’ that are similar to the speech bubbles in manga, as well as indicators that show HP and other information from game screens, and even the sound effects from games are used to match the psychology and actions of the characters.

Amy C. Chambers and R. Lyle Sakins characterise the narrative formed by these techniques as a participatory narrative that draws the audience into the culture to which the film refers. The frequent references to 8-bit video games and music, which were popular with the generation of the 1980s and 1990s (Generation X), allow the audience – which includes Generation X and beyond – to enjoy a nostalgic look back at the origins of these things(Chambers and Sakins, 2015). After the film was released, it was also embraced by modern subcultures, with people dressing up as the heroine Ramona Flowers. Scott Pilgrim has continued to create media mixes, from the original comic books to the film, the video game, and now the animation.

This post argues that the nature of the film’s comedy is achieved by self-referential use of the discrepancies between the various media embedded in the media ecosystem. The conventions of other media brought into the film seem to be used by a logic that differs from the conventional way of editing and technique. This film shows no concern for the coherence of time and space. In other words, as Shaviro says, it does not use continuity editing in the traditional sense, as seen in classical Hollywood films (Shaviro, 2016).

So, what logic is behind the use of these techniques and mise-en-scène? The techniques that are characteristic of this film include split-screen, jump cuts, and the use of frames that are continuous, like the frames of a comic strip or film strip. These technical features do not contribute to the audience’s immersion as a result of invisible editing. Rather, the excessive techniques are presentational for the audience, and serve to exaggerate the psychological states of the conventional characters.

They do not follow the characters’ psychological motivations or the development of the story based on some causal relationship. The sudden appearance of game screens in a film medium, or the coexistence of humans who seem to be game characters, is what gives this film its comedic nature. In this sense, this film is one that is made by using the conventions of new media in an unnatural way, while being fully aware of the conventions of traditional classical film. While the characteristics of other media are incorporated into the storytelling of Source Code and Edge of Tomorrow (which I discussed in my previous blog), in films like this one and Detention (2011), other media are used as a diagram to create a multilayered expression of the film, and the incongruity that arises between these layers – the discrepancy between the different media – is used in a self-referential way to characterise the comedic nature of these films.

Written by Takuya Nishihashi (33777985)

・References

Amy C. Chambers and R. Lyle Skains, “Scott Pilgrim vs. the multimodal mash-up: Film as participatory narrative,” Participations: Journal of Audience Reception Studies, 12(1), 2015, pp. 102-116.

Steven Shaviro, ‘Post-Continuity: An introduction’, Shane Denson and Julia Leyda eds., Post-cinema. Theorizing 21st-century film, Reframe Books, 2016, pp. 51-64.

Written by Takuya Nishihashi (33777985)

Leave a comment