Released in 2009, Coraline follows a young girl who discovers a parallel world that initially seems perfect but hides sinister intentions. As her Other Mother tries to trap her, Coraline must confront the darkness to save her real family.

Image source 1: Coraline movie poster (Link: https://www.amazon.co.uk/CORALINE-POSTER-APPROX-12X8-INCHES/dp/B00CPM6A82)

Although a stop-motion animation, Coraline embodies Shaviro’s (2010, p. 2) concept of the “post-cinematic,” bypassing conscious thought to provoke visceral reactions. Coraline is groundbreaking as the first film to combine traditional stop-motion techniques with visual effects and 3D printing. This blend of conventional filmmaking with post-cinematic methods enhances its ability to generate affect.

Coraline’s fathers food:

Image source 2, 3: Screenshots from Coraline (Selick, 2009)

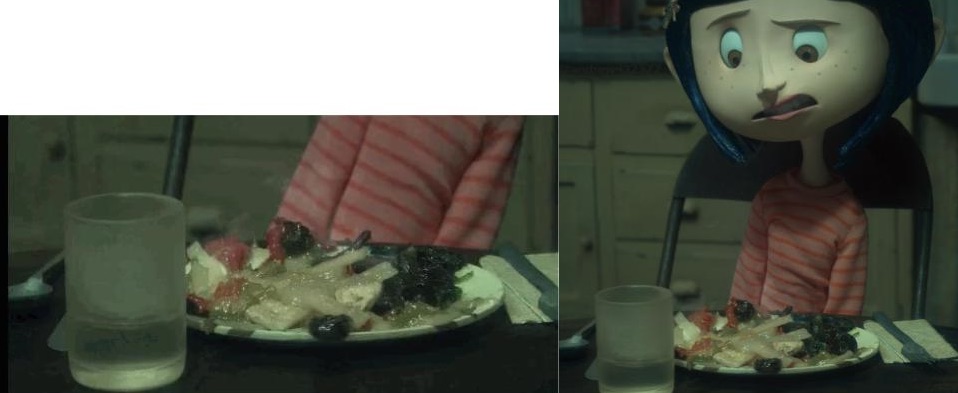

Other Mother’s food:

Image source 4, 5: Screenshots from Coraline (Selick, 2009)

Massumi (in Shaviro, 2010, p. 3) distinguishes affect—“primary, non-conscious, [and] asubjective”—from emotion, which is “conscious.” The two dinner scenes exemplify this: in the real world, Coraline’s father’s dull, slimy food stands in contrast to the Other Mother’s vibrant feast. Close-ups of the meals amplify these visceral reactions from viewers. As Shaviro adds, “emotion is affect captured” and contextualised through a subject. The affect of Coraline’s father’s food can be explained as disgust, while the affect of the Other Mother’s food evokes desire.

Shaviro (2010, p. 3) explains that “Films […] are machines for generating affect.” By choosing animation and combining it with visual effects, the filmmakers could control the look and feel of the film, intentionally creating affect.

Image source 6: Screenshots from Coraline (Selick, 2009)

Moreover, Coraline’s shifts between the real and Other World unsettle both her and the viewer. This mirrors our own transitions between physical and digital realities, fragmenting our sense of self. By reflecting on this post-cinematic instability, Coraline taps into the unease of modern existence.

The film’s innovative use of animation, alongside its fusion of traditional and post-cinematic techniques, demonstrates how affective storytelling manipulates audiences, leaving an indelible emotional imprint.

Bibliography:

Coraline (2009). Universal City, CA: Universal Studios.

Shaviro, S. (2010) ‘Post-Cinematic Affect: On Grace Jones, Boarding Gate and Southland Tales’, Film Philosophy 14.1.

Pauline Fontein

33754223

Leave a comment