BY LAI WEI 33870474

One of the most striking aspects of The Substance (2024), directed by Coralie Fargeat, is the extent to which its critique of female body anxiety extends beyond the screen and feeds back into the conditions of its own production. While the film presents itself as a satirical body-horror allegory about women pushed toward self-destruction by external pressures and the male gaze, its post-cinematic logic reveals a deeper contradiction: the very technologies it mobilizes to critique bodily perfection simultaneously reproduce it.

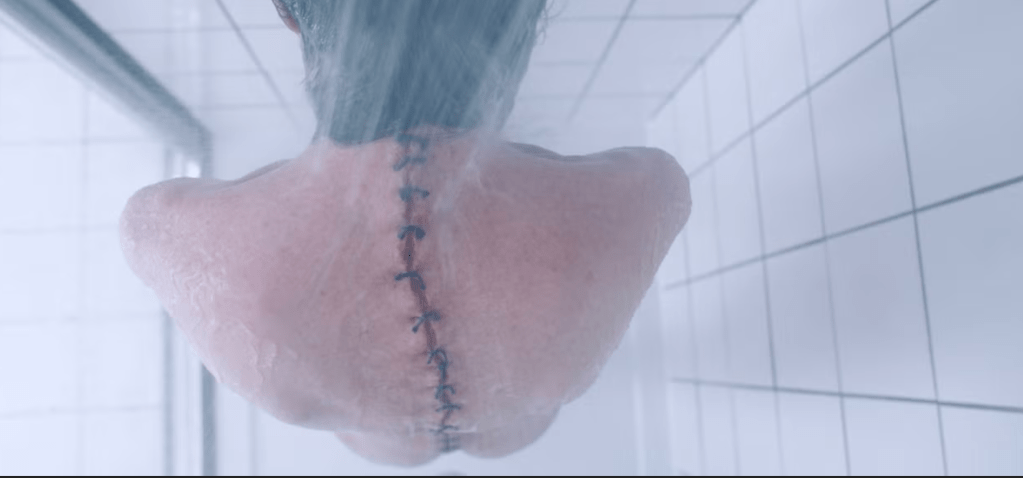

A frequently cited anecdote surrounding the film concerns Margaret Qualley, who was required to perform a nude mirror scene using seamlessly applied silicone prosthetics to create the illusion of fuller breasts. The irony is difficult to ignore. A film ostensibly about the psychological and physical anxiety caused by bodily “deficiency” resorts to digital and prosthetic enhancement to meet aesthetic expectations. As Qualley herself noted in interviews, the process was deeply uncomfortable—underscoring how post-cinematic cinema often displaces bodily anxiety rather than eliminating it. The body is no longer simply represented; it is technologically corrected, assembled, and optimized.

This contradiction becomes even more pronounced with the casting of Demi Moore, whose public history of cosmetic surgery and age-related scrutiny closely mirrors Elisabeth’s narrative arc. In The Substance, Elisabeth consumes a mysterious serum that splits her into two divergent bodily trajectories: one of hyper-youthful beauty and the other of accelerated, monstrous decay. Moore’s real-life experience with extreme bodily modification—and the resulting public discourse on “surgical excess”—renders her performance almost self-reflexive. The film thus operates within what Steven Shaviro calls a post-cinematic “structure of feeling,” where gut-level intensity and bodily transformation take precedence over psychological depth.

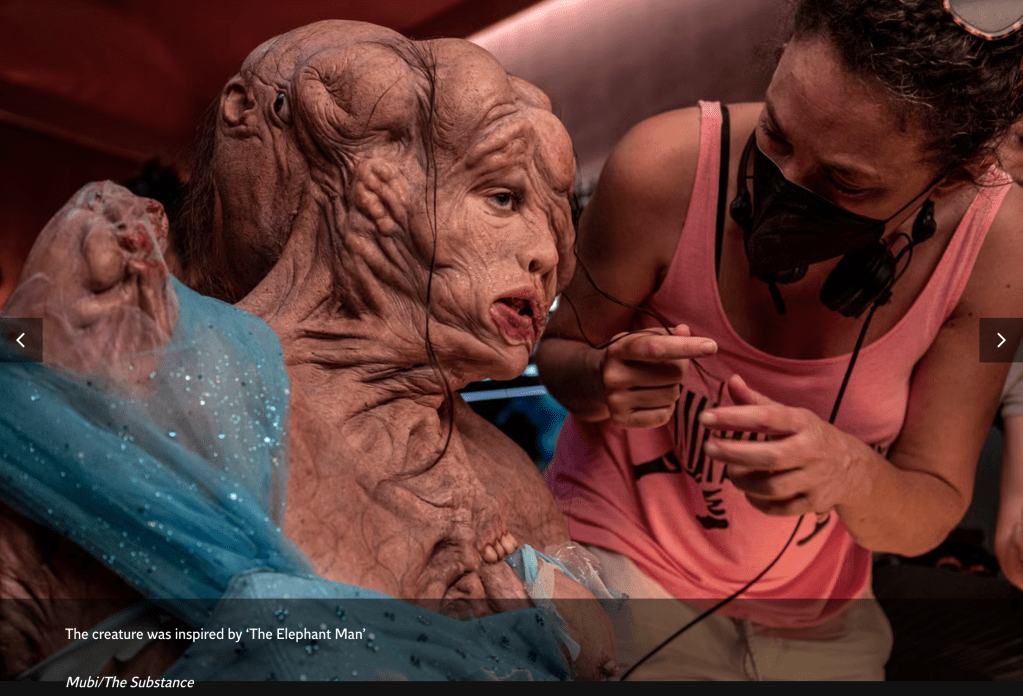

Unlike the classical body horror of David Cronenberg—which often foregrounds ambiguous desire and internal compulsion—The Substance externalizes conflict in stark, schematic terms. Elisabeth’s subjectivity is literalized as two separate bodies representing opposing social values: youthful desirability and abject excess. This binary logic aligns perfectly with post-cinematic aesthetics: inner conflict is no longer explored through gradual character development, but rendered as a spectacular, immediate transformation. The film’s power derives less from narrative complexity than from sensory overload, grotesque imagery, and the frenetic acceleration of bodily mutation.

In this sense, The Substance exemplifies a broader trend in contemporary festival cinema, where socially resonant themes—female bodily anxiety, aging, visibility—are translated into highly legible, entertainment-driven forms. As Shaviro argues, post-cinematic media often prioritize intensity, immediacy, and recognizability over ambiguity. The result is a cinema that is politically loud but psychologically thin. Characters become symbolic vessels rather than evolving subjects, and critique risks collapsing into spectacle.

Ultimately, The Substance succeeds as a post-cinematic artifact precisely because of its contradictions. Its reflexive entanglement of real and fictional body modification exposes the limits of contemporary cinematic critique. While the film condemns the violence of bodily perfection, it remains dependent on the very technological and aesthetic regimes that sustain that violence. In doing so, it reveals a central paradox of post-cinematic cinema: the more urgently it seeks to critique contemporary anxieties, the more tightly it becomes bound to the systems that produce them.

Reference:

1. Maira Butt, 2025, ‘Inside Demi Moore’s Oscar-nominated Substance transformation: 20,000 litres of ‘blood’ and 5 hours of make-up’

2. Shaviro, S. (2010), Post-Cinematic Affect: On Grace Jones, Boarding Gate and Southland Tales, Film-Philosophy, 14(1), pp. 1–102.

3. Williams, L. (1991) ‘Film bodies: Gender, genre, and excess’, Film Quarterly, 44(4), pp. 2–13.

4. Sobchack, V. (2004) Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Leave a comment